The are

12 basic principles of animation which were developed by

Frank Thomas and

Ollie Johnston in the

1930s. These principles came around as a desire to convey a new way of animating which seemed realistic in terms of how things moved, expressing a certain character's persona as a result.

(1)

SQUASH AND STRETCH.

This action gives the illusion of weight and volume to a character as it moves, potentially being the most important element as the principle of animation. The most common form of squash and stretch is in the animation of a bouncing ball as shown below:

As you can see in this picture the ball on the left maintains a constant speed as it bounces up and down which doesn't seem very realistic because this is not how a ball bounces in real life.

The ball on the right does squash and stretch but still doesn't depict the way a ball bounces up and down in real life as the speed is still constant throughout. However, the ball in the middle does convey realism because it does squash and stretch and it also changes momentum as it touches the ground and compared to when it reaches the top.

Even if the ball may not be an exact visual representation as to what a ball in real life looks like it still portrays realistic characteristics of movement as it bounces.

(2) ANTICIPATION.

This move prepares the audience for a major action that is about to happen. An example of this would be if a character was about to punch another character, he would not straight away flick his wrist up, a backward motion needs to occur before a forward one does, so in this case the character would bring his arm back in order to gain momentum for a strong punch, bringing a sense of realism in the animation.

Equally, this could happen when a person is about to jump: The character would firstly have to bend their knees in order to jump straight after, otherwise it would seem as if they are levitating off the floor. A backward reaction is normally always needed before a forward reaction. Here in an example of one:

(3) STAGING.

A pose or action should clearly communicate to the audience a character's emotions and persona. The use of long, medium, and close-up shots are also very effective in conveying the way a character's emotion and how they feel. There should not be too many actions and expressions going on at once as it would easily confuse the audience, making it harder to depict what is going on in the story. There should be careful thought on how the background is designed as you can't have an over-the-top background which will shift focus from the character or make them seem less important, unless that is the theme you're going for.

(4) STRAIGHT AHEAD AND POSE TO POSE ANIMATION.

There are two different animation methods to consider: pose to pose and straight ahead. Pose to pose animation involves defining a set of key poses which represent the extremes of a certain action, such as the beginning, middle and the end. The drawings in this method are related to each other in both size and action. This method also helps the in-between animators fill in the gap of the action knowing what the outcome of the action would be.

Straight ahead animation is actually working straight ahead right from the first drawing in the scene. Doing frame after frame, until he reaches the end of the scene getting new ideas as he draws. The point of the story is already known and the staging that needs to be done, but he has little plan on how it will turn out in the end since the time he starts drawing the first frame. The drawings and the actions are new, looking great as the animator keeps the entire process intuitive and creative.

(5) FOLLOW THROUGH AND OVERLAPPING ACTION.

Follow through: This is when a character is moving and their main body stops and all the other parts continue to catch up to the main body until it also finally stops such as arm, hair, clothing, earrings, tail, etc. Nothing all stops at the same time because it is not realistic.

Overlapping: This is when a character changes direction but the character's clothes/hair/tail continues forward. The character's clothes will only follow the character's main body a few frames later. Timing becomes critical to the effectiveness of drag and the overlapping action.

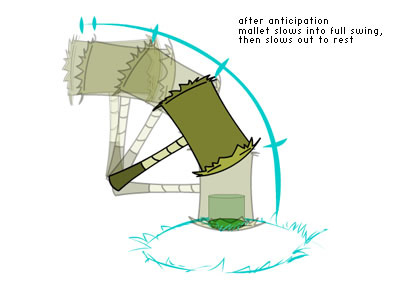

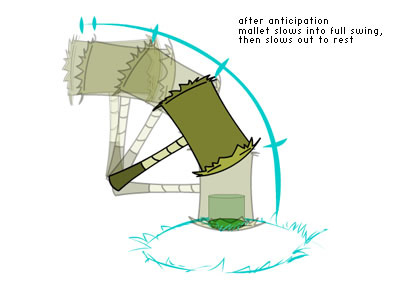

(6) SLOW-OUT AND SLOW-IN

This is when as a certain action starts there are more drawings at the beginning of the action, only a few in the middle and more again towards the end of the action. Fewer drawings make the action faster and more drawings make the action slower.

This gives off the realistic effect as when someone starts walking in real life, it isn't a constant speed throughout the whole action... You start slower and as you gain momentum you walk faster, until you come to a stop again where you begin to slow down instead of coming into a sudden halt. Here is an example:

(7) ARCS.

All actions carried out simply follow an arc, or circular path, as demonstrated in a human figure or animals. Arcs given animation a smoother and more realistic flow. All head, arms, leg or eye movements are portrayed on an arc.

<-- wrong correct -->

<-- wrong correct -->

(8) SECONDARY ACTION.

This occurs when an action directly results from another action to help increase complexity and adds more dimension to a character's animation. The secondary action should always subordinate to the primary action and never compete with the primary action in the scene.

Example: If a squirrel is running across a lawn the movement of the squirrel's legs (considered the primary action) would be animated to express the light nature of his character. The agile movement of the squirrel's tail (considered the secondary action) would have a separate and slightly different type of movement than his legs. The squirrel's tail is an example of secondary action.

(9) TIMING.

Timing, or the speed of an action is an important principle because it gives meaning to movement. The speed of an action defines how well an idea will be read to an audience.Timing can also define the weight of an object. Two similar objects can appear to seem very different weights by simply changing the time of the action as shown below:

The basics of it are that more drawings between poses slow and smooth the action, fewer drawings make the action faster and crisper and a variety of slow and fast timing within a scene adds interest to the movement.

(10) EXAGGERATION.

Exaggeration is the extremes of a facial feature, expressions, poses, attitudes and actions.Exaggeration does not just mean distorting the actions or objects, but the animator must carefully choose which properties to exaggerate. If only one thing is exaggerated then it may stand out too much. If everything is exaggerated then the entire scene may appear too unrealistic, the balance must be right.

Exaggeration is used in animation when trying to decide whether to be realistic or not by playing with the levels of exaggeration used an animator can achieve this. Exaggeration can be used on the character or elements in the storyline itself.

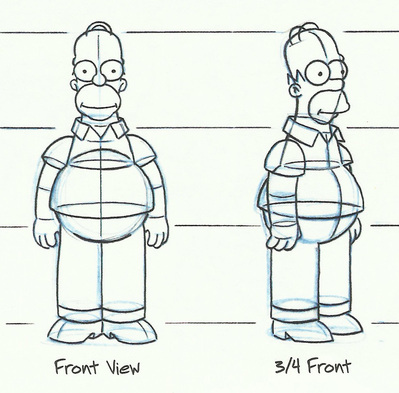

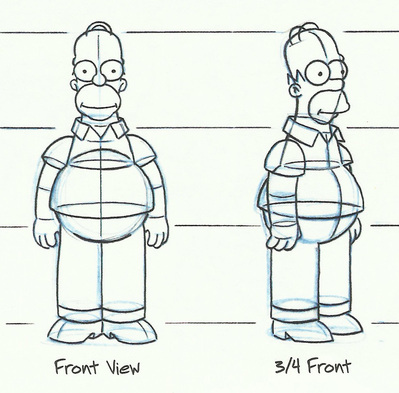

(11) SOLID DRAWING.

Solid drawing being able to draw your character from every angle in a believable manner so that they look alive. An animation looks more realistic when you take into account the angle you are looking at your character from and make sure the perspective is right. The basic principles of drawing form, weight, volume solidity and the illusion of 3D apply to animation as it does to academic drawing, as shown in the picture below of the world-famous 'The Simpsons' animation.

(12) APPEAL.

All characters must have appeal. Appeal was always very important from the start. It means anything that a person likes to see: a quality of charm, simplicity or a pleasing design. Your eye is always drawn to the figure that has appeal and once there it is held whilst appreciating what you are seeing. Both a hero or a villain can have appeal otherwise your eye is never concentrated on the protagonist.

<-- wrong correct -->

<-- wrong correct -->

No comments:

Post a Comment